August 19665

Shortly after Ernest Hemingway won the Nobel Prize in 1954, Mr. Manning, now executive editor of the ATLANTIC, visited the Hemingways in Cuba to collect first-person material for a magazine profile. From extensive notes taken during that visit and in subsequent talks with Hemingway in Cuba and New York, he has written one man's remembrance of Hemingway in his late years

Who in my generation was not moved by Hemingway the writer and fascinated by Hemingway the maker of his own legend? "Veteran out of the wars before he was twenty," as Archibald MacLeish described him. "Famous at twenty-five; thirty a master." Wine-stained moods in the sidewalk cafés and roistering nights in Left Bank boîtes.Walking home alone in the rain. Talk of death, and scenes of it, in the Spanish sun. Treks and trophies in Tanganyika's green hills. Duck-shooting in the Venetian marshes. Fighting in, and writing about, two world wars. Loving and drinking and fishing out of Key West and Havana. Swaggering into Toots Shor's or posturing in Life magazine or talking a verbless sort of Choctaw for the notebooks of Lillian Ross and the pages of the New Yorker.

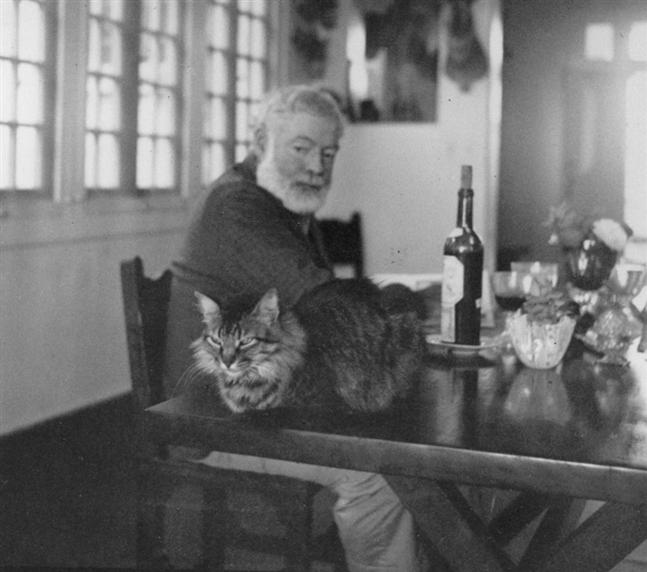

By the time I got the opportunity to meet him, he was savoring the highest moment of his fame -- he had just won the Nobel Prize for Literature -- but he was moving into the twilight of his life. He was fifty-five but looked older, and was trying to mend a ruptured kidney, a cracked skull, two compressed and one cracked vertebra, and bad burns suffered in the crash of his airplane in the Uganda bush the previous winter. Those injuries, added to half a dozen head wounds, more than 200 shrapnel scars, a shot-off kneecap, wounds in the feet, hands, and groin, had slowed him down. The casually comfortable Cuban villa had become more home than any place he'd had, and days aboard the Pilarwere his substitute for high adventure abroad.

In a telephone conversation between San Francisco de Paula and New York, Hemingway had agreed to be interviewed on the occasion of his Nobel award, but he resisted at first because one of the magazines I worked with had recently published a penetrating article on William Faulkner. "You guys cut him to pieces, to pieces," Hemingway said. "No, it was a good piece," I said, "and it would have been even better if Faulkner had seen the writer."

"Give me a better excuse," Hemingway said, and then thought of one himself. He saw the arrival of a visitor as an opportunity to fish on the Pilarafter many weeks of enforced idleness. "Bring a heavy sweater, and we'll go out on the boat," he said. "I'll explain to Mary that you're coming down to cut me up and feed me to William Faulkner."

A handsome young Cuban named René, who had grown up on Hemingway's place as his all-round handyman, chauffeur, and butler, was at Havana Airport to meet me and hustle my luggage, which included a batch of new phonograph records and, as a last-minute addition, a gift from Marlene Dietrich. On hearing that someone was going to Cuba to see her old friend, she sent along a newly released recording called "Shake, Rattle, and Roll," which now may be vaguely remembered as the Java man artifact in the evolution of popular rock 'n' roll. "Just like the Kraut," said Hemingway. He found the sentiment more appealing than the music.

A big man. Even after allowing for all the descriptions and photographs, the first impression of Hemingway in the flesh was size. He was barefoot and barelegged, wearing only floppy khaki shorts and a checked sport shirt, its tail tumbling outside. He squinted slightly through round silver-framed glasses, and a tentative smile, the sort that could instantly turn into a sneer or snarl, showed through his clipped white beard. Idleness had turned him to paunch, and he must have weighed then about 225 pounds, but there was no other suggestion of softness in the burly, broad-shouldered frame, and he had the biceps and calves of an N.F.L. linebacker.

"Drink?" Hemingway asked. The alacrity of the reply pleased him, and the smile broadened into a laugh. He asked René to mix martinis and said, "Thank God you're a drinking man. I've been worried ever since I told you to come down. There was a photographer here for three days a while ago who didn't drink. He was the cruelest man I've ever met. Cruelest man in the world. Made us stand in the sun for hours at a time. And he didn't drink." With stiff caution, he sank into a large overstuffed chair which had been lined back, sides, and bottom with big art and picture books to brace his injured back.

Hemingway sipped and said, "Now, if you find me talking in monosyllables or without any verbs, you tell me, because I never really talk that way. She [he meant Lillian Ross] told me she wanted to write a piece of homage to Hemingway. That's what she told me when I agreed to see her up in New York." He laughed. "I knew her for a long time. Helped her with her first big piece, on Sidney Franklin."

"I don't mind talking tonight," Hemingway said, "because I never work at night. There's a lot of difference between night thinking and day thinking. Night thoughts are usually nothing. The work you do at night you always will have to do over again in the daytime anyhow. So let's talk. When I talk, incidentally, it's just talk. But when I write I mean it for good."

The living room was nearly fifty feet long and high-ceilinged, with gleaming white walls that set off the Hemingways' small but choice collection of paintings (including a Miró, two by Juan Gris, a Klee, a Braque -- since stolen from the villa -- and five André Massons), a few trophy heads from the African safaris. In another room, near the entrance to a large tile-floored dining room, was an oil portrait of Hemingway in his thirties, wearing a flowing open-collar white shirt. "It's an old-days picture of me as Kid Balzac by Waldo Pierce," said Hemingway. "Mary has it around because she likes it."

He rubbed the tight-curled white beard and explained that he wore it because when clean-shaven his skin was afflicted with sore spots if he spent much time in the sun. "I'll clip the damned thing off for Christmas so as not to run against Santa Claus," he said, "and if I rest the hide a couple of weeks at a time, I may be able to keep it off. Hope so anyway."

INone large corner of the living room stood a six-foot-high rack filled with dozens of magazines and newspapers from the States, London, and Paris. In casual piles, books littered windowsills and tables and spilled a trail into two large rooms adjacent. One was a thirty-by-twenty-foot library whose floor-to-ceiling shelves sagged with books. The other was Hemingway's large but crowded bedroom study -- littered with correspondence in varied stages of attention or neglect. There were neat piles of opened letters together with stamped and addressed replies: cardboard boxes overflowing with the shards of correspondence that had been opened, presumably read, and one day might be filed; a couple of filing cabinets, whose mysteries probably were best known to a part-time stenographer the Hemingways brought in from Havana a day or two at a time when needed. There was also a large lion skin, in the gaping mouth of which lay half a dozen letters and a pair of manila envelopes. "That's the Urgent in-box," Hemingway explained.

The villa seemed awash with books -- nearly 400, including two dozen cookbooks, in Mary Hemingway's bedroom; more than 500, mostly fiction, history, and music, in the big sitting room; another 300, mostly French works of history and fiction, in an elegantly tiled room called the Venetian Room; nearly 2000 in the high-shelved library, these carefully divided into history, military books, biography, geography, natural history, some fiction, and a large collection of maps; 900 volumes, mostly military manuals and textbooks, history and geography in Spanish, and sports volumes, in Hemingway's bedroom. In the tall tower he kept another 400 volumes, including foreign editions of his own works, and some 700 overflowed into shelves and tabletops in the finca's small guesthouse. All the books, including Hemingway's collection of autographed works by many of his contemporaries, were impounded at the villa by the Castro regime, though Mrs. Hemingway was able to take away some of the paintings and personal belongings.

From the kitchen came sounds and smells of dinner in preparation. René emerged with two bottles of a good Bordeaux from a cellar that was steadily replenished from France and Italy. Evening sounds grew strident in the soft tropical outdoors. Distant dogs yelped. Near the house, a hoot owl broke into short, sharp cries. "That's the Bitchy Owl," Hemingway said. "He'll go on like that all night. He's lived here longer than we have.

"I respect writing very much," he said abruptly, "the writer not at all, except as the instrument to do the writing. When a writer retires deliberately from life or is forced out of it by some defect, his writing has a tendency to atrophy, just like a man's limb when it's not used.

"I'm not advocating the strenuous life for everyone or trying to say it's the choice form of life. Anyone who's had the luck or misfortune to be an athlete has to keep his body in shape. The body and mind are closely coordinated. Fattening of the body can lead to fattening of the mind. I would be tempted to say that it can lead to fattening of the soul, but I don't know anything about the soul." He halted, broodingly, as if reflecting on his own aches and pains, his too ample paunch, a blood pressure that was too high, and a set of muscles that were suffering too many weeks of disuse. "However, in everyone the process of fattening or wasting away will set in, and I guess one is as bad as the other."

He had been reading about medical discoveries which suggested to him that a diet or regimen or treatment that may work for one man does not necessarily work for another. "This was known years ago, really, by people who make proverbs. But now doctors have discovered that certain men need more exercise than others; that certain men are affected by alcohol more than others; that certain people can assimilate more punishment in many ways than others.

"Take Primo Carnera, for instance. Now he was a real nice guy, but he was so big and clumsy it was pitiful. Or take Tom Wolfe, who just never could discipline his mind to his tongue. Or Scott Fitzgerald, who just couldn't drink." He pointed to a couch across the room. "If Scott had been drinking with us and Mary called us to dinner, Scott'd make it to his feet, all right, but then he'd probably fall down. Alcohol was just poison to him. Because all these guys had these weaknesses, it won them sympathy and favor, more sometimes than a guy without those defects would get."

For a good part of his adult life Hemingway was, of course, a ten-goal drinker, and he could hold it well. He was far more disciplined in this regard, though, than the legend may suggest. Frequently when he was working hard, he would drink nothing, except perhaps a glass or two of wine with meals. By rising at about daybreak or half an hour thereafter, he had put in a full writing day by ten or eleven in the morning and was ready for relaxation when others were little more than under way.

As in his early days, Hemingway in the late years worked with painful slowness. He wrote mostly in longhand, frequently while standing at a bookcase in his bedroom; occasionally he would typewrite ("when trying to keep up with dialogue"). For years he carefully logged each day's work. Except for occasional spurts when he was engaged in relatively unimportant efforts, his output ran between 400 and 700 words a day. Mary Hemingway remembers very few occasions when it topped 1000 words. He did not find writing to be quick or easy. "I always hurt some," he remarked.

HEMINGWAY was capable of great interest in and generosity toward younger writers and some older writers, but as he shows in A Moveable Feast(written in 1957-1959 and finished in the spring of 1961), he had a curious and unbecoming compulsion to poke and peck at the reputations of many of his literary contemporaries. Gertrude Stein, Sherwood Anderson, T. S. Eliot, not to mention Fitzgerald, Wolfe, Ford Madox Ford, James Gould Cozzens, and others, were invariably good for a jab or two if their names came up. As for the critics -- "I often feel," he said, "that there is now a rivalry between writing and criticism, rather than the feeling that one should help the other." Writers today could not learn much from the critics. "Critics should deal more with dead writers. A living writer can learn a lot from dead writers."

Fiction-writing, Hemingway felt, was to invent out of knowledge. "To invent out of knowledge means to produce inventions that are true. Every man should have a built-in automatic crap detector operating inside him. It also should have a manual drill and a crank handle in case the machine breaks down. If you're going to write, you have to find out what's bad for you. Part of that you learn fast, and then you learn what's good for you."

What sort of things? "Well, take certain diseases. These diseases are not good for you. I was born before the age of antibiotics, of course.... Now take The Big Sky [by A. B. Guthrie]. That was a very good book in many ways, and it was very good on one of the diseases ... just about the best book ever written on the clap." Hemingway smiled.

"But back to inventing. In The Old Man and the Sea I knew two or three things about the situation, but I didn't know the story." He hesitated, filling the intervals with a vague movement of his hands. "I didn't even know if that big fish was going to bite for the old man when it started smelling around the bait. I had to write on, inventing out of knowledge. You reject everything that is not or can't be completely true. I didn't know what was going to happen for sure in For Whom the Bell Tolls or Farewell to Arms. I was inventing. "

Philip Young's Ernest Hemingway, published in 1953, had attributed much of Hemingway's inspiration or "invention" to his violent experiences as a boy and in World War I.

"If you haven't read it, don't bother," Hemingway volunteered. "How would you like it if someone said that everything you've done in your life was done because of some trauma. Young had a theory that was like -- you know, the Procrustean bed, and he had to cut me to fit into it."

During dinner, the talk continued on writing styles and techniques. Hemingway thought too many contemporary writers defeated themselves through addiction to symbols. "No good book has ever been written that has in it symbols arrived at beforehand and stuck in." He waved a chunk of French bread. "That kind of symbol sticks out like -- like raisins in raisin bread. Raisin bread is all right, but plain bread is better."

He mentioned Santiago, his old fisherman, in roughly these terms: Santiago was never alone because he had his friend and enemy, the sea, and the things that lived in the sea, some of which he loved and others he hated. He loved the sea, but the sea is a great whore, as the book made clear. He had tried to make everything in the story real -- the boy, the sea, and the marlin and the sharks, the hope being that each would then mean many things. In that way, the parts of a story become symbols, but they are not first designed or planted as symbols.

http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/65aug/6508manning2.htm

THE Bitchy Owl hooted the household to sleep. I was awakened by tropical birds at the dawn of a bright and promising day. This was to be Hemingway's first fishing trip on Pilar since long before his African crash. By six thirty he was dressed in yesterday's floppy shorts and sport shirt, barefooted, and hunched over his New York Times, one of the six papers he and Mary read every day. From the record player came a mixture of Scarlatti, Beethoven, Oscar Peterson, and a remake of some 1928 Louis Armstrong.

At brief intervals Hemingway popped a pill into his mouth. "Since the crash I have to take so many of them they have to fight among themselves unless I space them out," he said.

While we were breakfasting, a grizzled Canary Islander named Gregorio, who served as the Pilar's first mate, chef, caretaker, and bartender, was preparing the boat for a day at sea. By nine o'clock, with a young nephew to help him, he had fueled the boat, stocked it with beer, whiskey, wine, and a bottle of tequila, a batch of fresh limes, and food for a large seafood lunch afloat. As we made out of Havana Harbor, Gregorio at the wheel and the young boy readying the deep-sea rods, reels, and fresh bait-fish, Hemingway pointed out landmarks and waved jovially to passing skippers. They invariably waved back, occasionally shouting greetings to "Papa." He sniffed the sharp sea air with delight and peered ahead for the dark line made by the Gulf Stream. "Watch the birds," he said. "They show us when the fish are up."

Mary Hemingway had matters to handle at the finca and in the city, so she could not come along, but out of concern for Hemingway's health she exacted a promise. In return for the long-missed fun of a fishing expedition, he agreed to take it easy and to return early, in time for a nap before an art exhibit to which he and Mary had promised their support. He was in a hurry, therefore, to reach good fishing water. Gregorio pushed the boat hard to a stretch of the Gulf Stream off Cojimar. Hemingway relaxed into one of the two cushioned bunks in the boat's open-ended cabin.

"It's wonderful to get out on the water. I need it." He gestured toward the ocean. "It's the last free place there is, the sea. Even Africa's about gone; it's at war, and that's going to go on for a very long time."

The Pilar fished two rods from its high antenna-like outriggers and two from seats at the stern, and at Hemingway's instruction, Gregorio and the boy baited two with live fish carefully wired to the hooks, and two with artificial lures. A man-o'-war bird gliding lazily off the coast pointed to the first school of the day, and within an hour the Pilar had its first fish, a pair of bonito sounding at the end of the outrigger lines. Before it was over, the day was to be one of the best fishing days in many months, with frequent good runs of bonito and dolphin and pleasant interludes of quiet in which to sip drinks, to soak up the Caribbean sun, and to talk.

Sometimes moody, sometimes erupting with boyish glee at the strike of a tuna or the golden blue explosion of a hooked dolphin, and sometimes -- as if to defy or outwit his wounds -- pulling himself by his arms to the flying bridge to steer the Pilar for a spell, Hemingway talked little of the present, not at all of the future, and a great deal of the past.

He recalled when Scribner's sent him first galley proofs of For Whom the Bell Tolls. "I remember, I spent ninety hours on the proofs of that book without once leaving the hotel room. When I finished, I thought the type was so small nobody would ever buy the book. I'd shot my eyes, you see. I had corrected the manuscript several times but still was not satisfied. I told Max Perkins about the type, and he said if I really thought it was too small, he'd have the whole book reprinted. That's a real expensive thing, you know. He was a sweet guy. But Max was right, the type was all right."

"Do you ever read any of your stuff over again?"

"Sometimes I do," he said. "When I'm feeling low. It makes you feel good to look back and see you can write."

"Is there anything you've written that you would do differently if you could do it over?"

"Not yet."

New York. "It's a very unnatural place to live. I could never live there. And there's not much fun going to the city now. Max is dead. Granny Rice is dead. He was a wonderful guy. We always used to go to the Bronx Zoo and look at the animals."

The Key West days, in the early thirties, were a good time. "There was a fighter there -- he'd had one eye ruined, but he was still pretty good, and he decided to start fighting again. He wanted to be his own promoter. He asked me if I would referee his bout each week. I told him, 'Nothing doing,' he shouldn't go in the ring anymore. Any fighter who knew about his bad eye would just poke his thumb in the other one and then beat his head off.

"The fighter said, 'The guys come from somewhere else won't know 'bout my eye, and no one around here in the Keys gonna dare poke my eye.'

"So I finally agreed to referee for him. This was the Negro section, you know, and they really introduced me: 'And the referee for tonight, the world-famous millionaire, sportsman, and playboy, Mister Ernest Hemingway!"' Hemingway chuckled. "Playboy was the greatest title they thought they could give a man." Chuckle again. "How can the Nobel Prize move a man who has heard plaudits like that?"

Frequently a sharp cry from Gregorio on the flying bridge interrupted the talk. "Feesh! Papa, feesh!" Line would snap from one of the outriggers, and a reel begin to snarl. "You take him," Hemingway would say, or if two fish struck at once, as frequently happened, he would leap to one rod and I to the other.

For all the hundreds of times it had happened to him, he still thrilled with delight at the quivering run of a bonito or the slash of a dolphin against the sky. "Ah, beautiful! A beautiful fish. Take him softly now. Easy. Easy. Work him with style. That's it. Rod up slowly. Now reel in fast. Suave! Suave! Don't break his mouth. If you jerk, you'll break his mouth, and the hook will go."

When action lulled, he would scan the seascape for clues to better spots. Once a wooden box floated in the near distance, and he ordered Gregorio toward it. "We'll fish that box," he said, explaining that small shrimp seek shelter from the sun beneath flotsam or floating patches of seaweed and these repositories of food attract dolphin. At the instant the lures of the stern rods passed the box, a dolphin struck and was hooked, to be pumped and reeled in with the heavy-duty glass rod whose butt rested in a leather rod holder strapped around the hips.

He talked about the act of playing a fish as if it were an English sentence. "The way to do it, the style, is not just an idle concept. It is simply the way to get done what is supposed to be done; in this case it brings in the fish. The fact that the right way looks pretty or beautiful when it's done is just incidental."

Hemingway had written only one play, The Fifth Column. Why no others?

"If you write a play, you have to stick around and fix it up," he said. "They always want to fool around with them to make them commercially successful, and you don't like to stick around that long. After I've written, I want to go home and take a shower."

Almost absently, he plucked James Joyce out of the air. "Once Joyce said to me he was afraid his writing was too suburban and that maybe he should get around a bit and see the world, the way I was doing. He was under great discipline, you know -- his wife, his work, his bad eyes. And his wife said, yes, it was too suburban. 'Jim could do with a spot of that lion-hunting.' How do you like that? A spot of lion-hunting!

"We'd go out, and Joyce would fall into an argument or a fight. He couldn't even see the man, so he'd say, 'Deal with him, Hemingway! Deal with him!' " Hemingway paused. "In the big league it is not the way it says in the books."

Hemingway was not warm toward T. S. Eliot. He preferred to praise Ezra Pound, who at that time was still confined in St. Elizabeth's mental hospital in Washington. "Ezra Pound is a great poet, and whatever he did, he has been punished greatly, and I believe should be freed to go and write poems in Italy, where he is loved and understood. He was the master of Eliot. I was a member of an organization which Pound founded with Natalia Barney in order to get Eliot out of his job in a bank so he could be free to write poetry. It was called Bel Esprit. Eliot, I believe, was able to get out of his job and edit a review and write poetry freely due to the backing of other people than this organization. But the organization was typical of Pound's generosity and interest in all forms of the arts regardless of any benefits to himself or of the possibilities that the people he encouraged would be his rivals.

"Eliot is a winner of the Nobel Prize. I believe it might well have gone to Pound, as a poet. Pound certainly deserved punishment, but I believe this would be a good year to release poets and allow them to continue to write poetry.... Ezra Pound, no matter what he may think, is not as great a poet as Dante, but he is a very great poet for all his errors."

DUSK was coming when the Pilar turned toward Havana Harbor, its skipper steering grandly from the flying bridge. What remained of the bottle of tequila and a half of lime rested in a holder cut into the mahogany rail near the wheel. "To ward off sea serpents," Hemingway explained, passing the bottle for a ceremonial homecoming swig.

At the docks, René reported that the gallery opening had been postponed. Hemingway was overjoyed. "Now we can relax for a while and then get some sleep. We went out and had a good day and got pooped. Now we can sleep."

Hemingway's good spirits on his return helped to diminish his wife's concern about his over-extending himself. She served up a hot oyster stew, and later, clutching an early nightcap, Hemingway sprawled with pleased fatigue in his big armchair and talked of books he had recently read. He had started Saul Bellow's The Adventures of Augie March, but didn't like it. "But when I'm working," he said, "and read to get away from it, I'm inclined to make bad judgments about other people's writing." He thought Bellow's very early book, Dangling Man, much better.

One of the post-war writers who had impressed him most was John Horne Burns, who wrote The Gallery and two other novels and then, in 1953, died in circumstances that suggested suicide. "There was a fellow who wrote a fine book and then a stinking book about a prep school, and then he just blew himself up," Hemingway mused, adding a gesture that seemed to ask, How do you explain such a thing? He stared at nothing, seeming tired and sad.

"You know," he said, "my father shot himself."

There was silence. It had frequently been said that Hemingway never cared to talk about his father's suicide.

"Do you think it took courage?" I asked.

Hemingway pursed his lips and shook his head. "No. It's everybody's right, but there's a certain amount of egotism in it and a certain disregard of others." He turned off that conversation by picking up a handful of books. "Here are a few things you might like to look at before you turn off the light." He held out The Retreat, by P. H. Newby, Max Perkins' selected letters, The Jungle Is Neutral, by Frederick S. Chapman, and Malcolm Cowley's The Literary Situation.

By seven the next morning a rabble of dogs yipped and yelped in the yard near the finca's small guesthouse. rené had been to town and returned with the mail and newspapers. Hemingway, in a tattered robe and old slippers, was already half through the Times.

"Did you finish the Cowley book last night?" he asked. "Very good, I think. I never realized what a tough time writers have economically, if they have it as tough as Malcolm says they do."

He was reminded of his early days in Paris. "It never seemed like hardship to me. It was hard work, but it was fun. I was working, and I had a wife and kid to support. I remember, first I used to go to the market every morning and get the stuff for Bumby's [his first son, John] bottle. His mother had to have her sleep." Lest this should be taken as a criticism, he added, "That's characteristic, you know, of the very finest women. They need their sleep, and when they get it, they're wonderful."

Another part of the routine in the Paris days, to pick up eating money, was Hemingway's daily trip to a gymnasium to work as a sparring partner for fighters. The pay was two dollars an hour. "That was very good money then, and I didn't get marked up very much. I had one rule: never provoke a fighter. I tried not to get hit. They had plenty of guys they could knock around."

He reached for the mail, slit open one from a pile of fifteen letters. It was from a high school English teacher in Miami, Florida, who complained that her students rarely read good literature and relied for "knowledge" on the movies, television, and radio. To arouse their interest, she wrote, she told them about Hemingway's adventures and pressed them to read his writings. "Therefore, in a sense," she concluded, "you are the teacher in my tenth grade classroom. I thought you'd like to know it." Hemingway found the letter depressing: "Pretty bad if kids are spending all that time away from books."

The next fishing expedition was even better than the first -- fewer fish, but two of them were small marlin, one about eighty pounds, the other eighty-five, that struck simultaneously and were boated, Hemingway's with dispatch, the second at a cost of amateurish sweat and agony that was the subject of as much merriment as congratulations. It was a more sprightly occasion, too, because Mary Hemingway was able to come along. A bright, generous, and energetic woman, Hemingway's fourth wife cared for him well, anticipated his moods and his desires, enjoyed and played bountiful hostess to his friends, diplomatically turned aside some of the most taxing demands on his time and generosity. More than that, she shared his love and the broad mixture of interests -- books, good talk, traveling, fishing, shooting -- that were central to Hemingway's life. His marriage to her was plainly the central and guiding personal relationship of his last fifteen years.

Hemingway gazed happily at the pair of marlin. "We're back in business," he said, and gave Mary a hug. "This calls for celebration," said Mary.

"Off to the Floridita," said Hemingway.

The Floridita was once one of those comfortably shoddy Havana saloons where the food was cheap and good and the drinking serious. By then, enjoying a prosperity that was due in no small part to its reputation as the place you could see and maybe even drink with Papa Hemingway, it had taken on a red-plush grandeur and even had a velvet cord to block off the dining room entrance. "It looks crummy now," Hemingway said, "but the drinking's as good as ever."

The Floridita played a special role in Hemingway's life. "My not living in the United States," he explained, "does not mean any separation from the tongue or even the country. Any time I come to the Floridita I see Americans from all over. It can even be closer to America in many ways than being in New York. You go there for a drink or two, and see everybody from everyplace. I live in Cuba because I love Cuba -- that does not mean a dislike for anyplace else. And because here I get privacy when I write. If I want to see anyone, I just go into town, or the Air Force guys come out to the place, naval characters and all -- guys I knew in the war. I used to have privacy in Key West, but then I had less and less when I was trying to work, and there were too many people around, so I'd come over here and work in the Ambos Mundos Hotel."

The Floridita's bar was crowded, but several customers obligingly slid away from one section that had been designated long before by the proprietor as "Papa's Corner." Smiles. "Hello, Papa." Handshakes all around. "Three Papa Dobles," said Hemingway, and the barkeep hastened to manufacture three immense daiquiris according to a Floridita recipe that relies more on grapefruit juice than on lemon or lime juice. The Papa Doble was a heavy seller in those days at $1.25, and a bargain at that.

Two sailors off a U.S. aircraft carrier worked up nerve to approach the author and ask for an autograph. "I read all your books," said one of them.

"What about you?" Hemingway said to the other.

"I don't read much," the young sailor said.

"Get started," Hemingway said.

The Floridita's owner appeared, with embraces for the Hemingways and the news that he was installing a modern men's room. Hemingway noted sadly that all the good things were passing. "A wonderful old john back there," he said. "Makes you want to shout: Water closets of the world unite; you have nothing to lose but your chains."

THERE were some other chances in later years to talk with Hemingway, in Cuba and New York, and there were a few letters in between -- from Finca Vigia or Spain or France, or from Peru, where he went to fish with the Hollywood crew that made the film of The Old Man and the Sea."Here's the chiropractor who fixed up my back," said the inscription on a postcard-size photograph from Peru showing him and an immense marlin he landed off Puerto Blanco.

Trips to New York grew less frequent and did not seem to amuse or entertain him. Unlike the old days and nights at Shor's or Twenty-one, he later usually preferred to see a few friends and dine in his hotel suite. Top health never really seemed to come back to him. He was having trouble with his weight, blood pressure, and diet. He was still working, though, as the stylishly written pages of A Moveable Feast show. (How much else he was producing then is not clear. Mrs. Hemingway, together with Scribner's and Hemingway's authorized biographer, Carlos Baker, and his old friend Malcolm Cowley, is sifting a trunkload of manuscripts that include some short stories, several poems, some fragments of novels, and at least one long completed novel about the sea -- written to be part of a trilogy about land, sea, and air.)

His curiosity about the world, about people, about the old haunts (that word probably ought to be taken both ways) remained zestful, and so did his willingness to talk books and authors.

Once NBC did an hour-long radio documentary featuring recollections by many people who knew Hemingway, including some who were no longer friends. Sidney Franklin's comments annoyed him. "I never traveled with Franklin's bullfighting 'troupe,'" Hemingway said. "That is all ballroom bananas. I did pay for one of his operations, though, and tried to get him fights in Madrid when no promoter would have him, and staked him to cash so he wouldn't have to pawn his fighting suits." Max Eastman had retold on the broadcast his version of the memorable fight between him and Hemingway at Scribner's over Eastman's reflections on whether Hemingway really had any hair on his chest. "He was sort of comic," said Hemingway. "There used to be a character had a monologue something like Listen to What I Done to Philadelphia Jack O'Brien. Eastman is weakening though. In the original version he stood me on my head in a corner, and I screamed in a high-pitched voice."

Hemingway added: "None of this is of the slightest importance, and I never blow the whistle on anyone, nor dial N for Narcotics if I find a friend or enemy nursing the pipe."

On a later occasion, a dean of theology wrote in the New Republic an article entitled "The Mystique of Merde" about those he considered to be "dirty" writers, and put Hemingway near the top of his list. A newsmagazine reprinted part of the article, and when he read it, Hemingway, then in Spain, addressed as a rebuttal to the dean a hilarious short lecture on the true meaning of the word merde and its use as a word of honor among the military and theatrical people. It is, Hemingway explained, what all French officers say to one another when going on an especially dangerous mission or to their deaths, instead of au revoir, good-bye, good luck old boy, or any similar wet phrases. "I use old and bad words when they are necessary, but that does not make me a dirty writer," he said. For the dean, he had a dirty word. But he did not send the note to him; the writing of it turned his irritation into a shrug.

THE Hemingways left Cuba in July of 1960 and went to Key West. From there, with luggage that filled a train compartment, they went to New York to live for a while in a small apartment. Later they moved to the new place Hemingway had bought in Ketchum, Idaho, close to the kind of shooting, fishing, walking that had beguiled him as a young boy in upper Michigan. He went to Spain for six weeks that summer to follow his friend Ordoñez and his rival, Dominguin, in their mano a manotour of bullfights and to write The Dangerous Summer, bullfight pieces commissioned by Life magazine. I have the impression that he didn't think very much of them, but he didn't say. His spirits seemed low after that and ostensibly stayed that way, though he apparently kept at work out in Ketchum almost until the day his gun went off.

The rereading of the notes and letters from which these glimpses of Hemingway are drawn -- for glimpses are all they are -- induces a curious thought: It is possible that to have known him, at least to have known him superficially and late in his life, makes it more rather than less difficult to understand him.

He made himself easy to parody, but he was impossible to imitate. He sometimes did or said things that seemed almost perversely calculated to obscure his many gallantries and generosities and the many enjoyments and enthusiams he made possible for others. He could be fierce in his sensitivity to criticism and competitive in his craft to the point of vindictiveness, but he could laugh at himself ("I'm Ernie Hemorrhoid, the poor man's Pyle," he announced when he put on his war correspondent's uniform) and could enjoy the pure pride of believing that he had accomplished much of what he set out to do forty-five years before in a Parisian loft.

The private Hemingway was an artist. The public Hemingway was an experience, one from which small, sharp remembrances linger as persistently as the gusty moments:

A quiet dinner in New York when he remarked out of a rueful silence, and with a hint of surprise, "You know -- all the beautiful women I know are growing old."

A misty afternoon in Cuba when he said, "If I could be something else, I'd like to be a painter."

A letter from the clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where doctors were working him over: he reported "everything working o.k." -- the blood pressure down from 250/125 to 130/80, and the weight down to 175 pounds, low for that big frame. He was two months behind, he said, on a book that was supposed to come out that fall -- the fall of 1961.

And last of all, a Christmas card with the extra message in his climbing script: "We had fun, didn't we?"

Copyright © 1965 by Robert Manning. All rights reserved.The Atlantic Monthly; August 1999; Hemingway in Cuba - 65.08 (Part Two); Volume 216, No. 2; page 101-198. Copyright © 1965 by Robert Manning. All rights reserved.The Atlantic Monthly; August 1965; Hemingway in Cuba - 65.08; Volume 216, No. 2; page 101-108.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

HELP-Matrix Humane-Liberation-Party Blog ~ http://help-matrix.blogspot.com/ ~

Humane-Liberation-Party Portal ~ http://help-matrix.ning.com/ ~

@Peta_de_Aztlan Blog ~ http://peta-de-aztlan.blogspot.com/ ~ @Peta_de_Aztlan

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please keep comments humane!