Bobby Seale was the chairman and co-founder, along with Huey Newton, of the Black Panther Party, an organization formed in 1966 to guard against police brutality in black neighborhoods and provide social services.

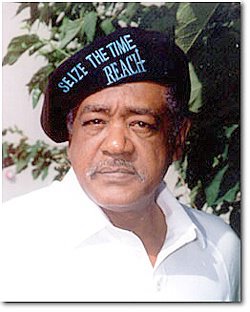

Bobby Seale was the chairman and co-founder, along with Huey Newton, of the Black Panther Party, an organization formed in 1966 to guard against police brutality in black neighborhoods and provide social services. Eventually the party developed into a militant Marxist revolutionary group with thousands of members in several major cities. In 1969, Seale, as one of the "Chicago Eight," was charged with conspiracy to incite riots during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Charges against him were eventually dropped, but not before he had been bound and gagged to silence his courtroom outbursts. In 1970-71 he was tried for the torture-murder of former Panther Alex Rackley, who was suspected of being a police informant. That trial ended in a hung jury, and afterward, Seale moderated his more militant views, leaving the Panthers altogether in 1974. He was interviewed for the COLD WAR series in August 1996.

On the origins of the Black Panther Party:

We had written the 10-point program -- 10 points of what we want, 10 points of what we believe -- before we even had a name. We'd written it in the "War on Poverty" office in Oakland, California. I worked there. Most people don't know I was actually employed by the city government of Oakland, California when we actually founded the party. Huey Newton was in night law school. ...

One day I received a two- or three-page stapled piece of information from the Mississippi Lowndes County Freedom Organization, and they had a logo of a charging panther, a silhouetted kind of logo, and I asked Huey, I says, "I wonder why these guys have this black panther here." And at another point that day, Huey says, "You know, I think the nature of a panther is that if you push that black panther into a corner, he will try to go left to get out of your way. And if you keep him there, then he's going to try to go right to get out of your way. And if you keep oppressing him and pushing him into that corner, sooner or later that panther's going to come out of that corner to try to wipe out whoever's oppressing it in the corner."

I says, "Huey, that's just like us, that's just like black people." He says, "What are you saying?" "I'm saying: man, you're the one who's always running around talking about how the peaceful demonstrators' constitutional rights are being violated" -- you know, because Huey was into law, you know. ... I says, "Black people [are being] pushed in the corner, just like the panther!" ... Huey says, "Oh, I see what you mean. So if we're going to have a political party, we should call it the Black Panther Party?" I said, "Yeah, right, the Black Panther Party. We're just like the panther, pushed in the corner, trying to go left, trying to go right. But now," I said, "but now we are..." And Huey's saying, "... getting ready to come out of that corner." "Right," I says. So this is really the way we wound up naming our organization the Black Panther Party. ... Our position was: "If you don't attack us, there won't be any violence; [but] if you bring violence to us, we will defend ourselves."

On the Panthers' 10-point program:

The first point was we wanted power to determine our own destiny in our own black community. And what we had done is, we wanted to write a program that was straightforward to the people. We didn't want to give a long dissertation. "Power" was related to "black power," but we had set the word "black" aside and we wanted to get a functional definition of "power." So prior to writing this first point, Huey came up with this: "Power is the ability to define a phenomenon, then in turn make it act in a desired manner." ...

So when we wrote point No. 1, without going into that dissertation, we just said we wanted power to determine our destiny in our own black community; we didn't say we wanted "black power," we said we wanted "power" -- because we were heading in the direction of a class analysis rather than any kind of naive nationalistic analysis. This is where we were coming from.

Point No. 2, we were straightforward: we want decent housing, shelter for human beings. Point No. 3: we want full employment for our people. Point No. 4: we want decent education that teaches about our true history and our true selves. Point No. 5: at the time we wanted an end to the robbery of the black community by the white racist coppers. Point No. 6 (the first one we wrote): we wanted all black men and women to be exempt from any military service. Point No. 7, of course, was: we want an immediate end to police brutality and the murder of black people in our black community. Point No. 8 had to do with: all blacks who have already been tried by all-white juries have a right to another trial. Point No. 9 was also about the courts and fair treatment and constitutional rights in the courts. And 10 was really a summary: we said we wanted land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

We later attached a paraphrasing of the first two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America at the tail end of point No. 10. And then, in another point, we added a call for a United Nations-supervised plebiscite for the determination of the will of African-American people in America.

On the Black Panthers and Marxism:

Marxism didn't even come into play with our organization until we picked up a red book one day. But the Black Panther Party had nothing to do with it; it didn't evolve out of Marxism. ... From 1962-1965, the Black Panther Party was based on a complete study and research of African and African-American people's history of struggle. That's truly what it came out of. If you notice, in our 10-point platform and program we make no Marxist statements. ...

I think we were about five months old, and one day Huey had an idea how we could raise some money. And what happens here is that Huey calls up and says, "How much money have you got?" I say, "I don't know; a hundred or so dollars." He says, "Come on over. I know how we can raise some money to pay some rent and buy some more shotguns." And so I picked him up [and he] says, "Let's go a place called the China Bookstore." When we got there, this particular bookstore sold all kinds of publications from China, Hong Kong, Red China, whatever, OK? Taiwan, whoever. And he says, "The Red Book," he says, "do you remember seeing ...?" I says, "I remember seeing something about Mao Tse-tung," I said, "I saw it two or three times, and millions of people were holding this little red book up telling the thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-tung." He says, "I just found out we could get these things here for 25 cents." And he says, "I'm sure we could sell them at the University of California, Berkeley, for a buck." ...

So I says, "OK, [Huey]," I says, "let's get a couple of hundred books." So we got a couple of hundred books ... and went to this gate at the University of California, at Berkeley: "Get your red book, the thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-tung! One buck!" They went like hot cakes. I'm talking about in a matter of an hour all 200 or so books were gone. We jumped in the car, ran back, got some more books, came back up, sold a couple of hundred more, ran and bought a shotgun, went and paid some phone bills, paid the rent up. And this was like, now, we had not read this book. I mean, the next thing you know, we're selling books [right and left]. ... We were busy selling the book for the dollars to get our rent, to buy more shotguns, to buy more books for the reading list for the party members that we had going.

And one day we opened it up, and says, "Hey, man, this is pretty good stuff. Chairman Mao Tse-tung says you should not steal a needle and piece of thread from the people." I says, "That's something we could teach the party members." Because we were a young organization: we weren't more than about four or five months old. And that's where we began to have what we would call a lot of study in that [Marxist] direction. We had read a little Che Guevara prior to that, but we weren't that highly influenced by [him]. ... In terms of the concept of economics at that time, what I developed best was a concept of community-controlled cooperatives in the black community, which largely I picked up from W.E.B. Dubois. So I mean, I sort of got there from W.E.B. Dubois and a few other reads. But Marxist-Leninism per se was really a latter development: not until 1968 that we really considered the Red Book required reading.

On the Black Panthers and firearms:

Prior to us patrolling the police with guns and law books and tape recorders -- we always had law books and tape recorders with us when we patrolled the police -- there was a group in Los Angeles that had attempted to observe the police a year before we did, in the fall of 1965, following the Watts riots down in Los Angeles, California. This group had law books and tape recorders, but they did not have any guns [while] observing the police because they did not want to see another Watts riot occur, [even though] what had caused the Watts riot was a vicious act of police brutality in the first place. After two or three months, they were jumped on and beat up by the police in Los Angeles, their law books taken and torn up, their tape recorders and their walkie-talkies smashed up, and dragged downtown and locked up.

Huey is in night law school when we read about this in January of 1966. Remember, the Black Panther Party didn't start till October of 1966. And Huey said that the police had violated the rights of the people; because Huey, being in night law school, was always arguing about your constitutional rights, the First Amendment, the right to peacefully assemble. ... Patrolling and observing the police, with no guns, was a peaceful assertion; but yet violence was heaped upon them. Two, we knew that if we're going to go out here, we'd better take a position like Malcolm X's saying: that self-defense is an act of intelligence. The guns are not there to just randomly kill anybody. That was not it. But the guns were there [for] a political organization who would be protesting white racism, racism and exploitation, etc. etc.; [and] once we start doing that, we're [liable] to get attacked. So we take the position of, one, defending ourselves. Two, since they'd already jumped on the L.A. group, Community Alert Patrol (CAP), a year before us, we went and did the same exact thing that the CAP organization had done a year before: law books, tape recorders, walkie-talkies, the whole bit, except we put uniforms on, black berets, black slacks, shined black shoes, nice black gloves, blue shirts, etc. We knew the law [and had our] 10-point programs. And of course, what we really wanted to do was capture the imagination of the black community, so that we could better organize them into a political electoral machine.

So the first issue we took up was the observation of the police, because that was what we had found from the community: "If you can do something about these racist police brutalizing us, it would be a good organization," the people told us. So we went out there very disciplined and very organized, to observe the cops with these loaded shotguns -- all of our guns were loaded. We'd researched every law on the guns; we knew that under California law, as long as the guns were not concealed, they were not illegal. [Also], if you were riding in a car, you could never have a live round in the chamber of a rifle or a shotgun. That same law did not apply to handguns: you could have a live round in the chamber of a handgun while riding in a car. Two, that when you get out of the car, and if you're just walking around with your gun, you cannot point a loaded weapon at a person, because under Californian law it'd constitute an assault with a deadly weapon; and that if you did point it, as Huey had researched it, it has to be in active self-defense, if somebody is ready to do you bodily harm. Now we had all these laws down with the guns.

On the one hand, the guns were there to help capture the imagination of the people. But more important, since we knew that you couldn't observe the police without guns, we took our guns with us to let the police know that we have an equalizer and we're going to "exercise," as Huey used to say, "this constitutional right to observe you, whether you like it or not." ...

In doing that, the people in the community observing us -- wow, we were like heroes, to stand there and observe the police, and the police were scared to move upon us. And then Huey had this great ability to articulate, because Huey was precise. Me, I'm more grass-rootsy in the way I express myself. But the police at one point says, "You have no right to observe me!" Huey says, "No, a California State Supreme Court ruling states that every citizen has the right to stand and observe a police officer carrying out his duty, as long as they stand a reasonable distance away. A reasonable distance in that particular ruling was constituted as eight to 10 feet. I'm standing approximately 20 feet from you, and I'll observe you whether you like it or not."

On Vietnam:

We jumped into the protest of Vietnam before the Black Panther Party ever started, before the Black Panther Party was even thought of. In fact, it was late 1965 and 1966 that the anti-Vietnam War, anti-draft to the Vietnam War protest started at University of California, Berkeley. What happened is, by 1966, us students who knew our history ... we knew that in the Civil War there was over 160-some thousand black men who fought in the Civil War with the North against the South, and 30-some thousand had died; we knew that over 350,000 black men had fought in World War I; we knew that over 850,000 black men had fought in World War II; we knew that black men were proliferating in the Korean conflict war. So now here I am coming with all this African-American history consciousness, with some kind of class analysis, but not necessarily Marxist-Leninist, and here I am looking at, in 1965 and 1966, we black students at Merritt College begin to say, "Why should we fight in the war any more? This country's government do not recognize our constitutional democratic human rights," I used to say. ...

Before the Black Panther Party was even conceived of we had an anti-war rally with a focus on the fact that 26-28 percent of the people who were dying on the front lines in Vietnam were black Americans, whose same rights were not being recognized in this country. And the whole focus was "Down with the war!" and "Black people do not serve in the military." ... So later, when we wrote the 10-point platform, [point] No. 6 says: we want all black men and women to be exempt from any military service to fight in Vietnam or whatever.

If we were supposed to be 12 percent of the population, why was 28 to 29 percent of those dying in the front lines black Americans? Why? And then our rights are not being recognized by this government? Screw you! You know. (Laughs) Down with the pig power structure!

On the FBI:

I knew they were watching us. ... They heavily focused in on us when we started to grow so rapidly. We began to grow rapidly really after Martin Luther King was killed. ... With Martin Luther King's death, by June, my party was jumping by leaps and bounds. In a matter of six months, we swelled; in 1968, from 400 members to 5,000 members and 45 chapters and branches. ... Our newspaper swells to over 100,000 circulation. By mid-1969, we [have] 250,000 circulation.

Why [did] the FBI [come] down on us? We started those working coalitions with other organizations at the beginning of 1968. Those coalitions solidified themselves. We had the Peace and Freedom Party working in coalition with the Black Panther Party; SDS: Students for a Democratic Society, all the anti-war movement people; numerous other organizations. In late 1968, we had a working coalition with the Poor People's March through Rev. Ralph Abernathy, with SCLC; we had a coalition with the Brown Berets, the Chicano organization, Cesar Chavez and others in the farm labor [movement]; AIM: American and Indian Movement; Young Puerto Rican Brothers, the Young Lords -- we coalesced with everybody, you see. Because remember, we were dealing with "all power to all the people," not just black power. ...

So, with the Breakfast for Children Program spreading across the country, getting a lot of media play, the Preventative Medical Health Care Clinics, the doctors, the medics -- I mean, this is authentic medicine, preventative medical health care clinics, the people donating their time. We got 5,000 full-time working members in the Black Panther Party, mostly college students; these were college students: I would say 60 percent of them were college students from after Martin Luther King was killed, because they were so upset and so mad that they killed Martin Luther King, they postponed their college education and said, "I'm joining the Black Panther Party." ...

This is what scared the FBI; to a point that our newspaper, beginning in 1969, we would ship 10,000 to this office, 10,000 or 5,000 to this office, through air freight, [and] when we went to the air freight place, they would soak our newspapers down. ... In the beginning of 1969, the polls came out that 90 percent of the black community supported the Black Panther Party because they understood the Breakfast Program, the Preventative Health Care Clinics, and they loved reading the Black Panther Party newspaper because it gave them another understanding of what civil and human rights was about. A couple of months after that, J. Edgar Hoover says: "The Black Panthers are the greatest threat to the internal security of America, and by the end of this year we'll be rid of the threat and this menace of the Black Panther Party."

Then a big news came about the Breakfast Program. J. Edgar Hoover jumped up and said: "The Breakfast for Children Program of the Black Panther Party is communist-inspired, and we need to get rid of it!" This was laying the foundation. Remember, the FBI, with COINTELPRO (COINTELPRO stood for Counter-Intelligence Program; that's an FBI term, not our term) ... they set it up, working with local law enforcement agencies, to attack every Black Panther Party office in the year of 1969. That was the year they attacked our offices; that was the year when most of the shootouts came. By the end of 1969, I had 29 Black Panther Party members dead. There were 14 policemen dead also in those attacks on our offices and our houses. I had 60-some-odd wounded Black Panther Party members; there were 30-some-odd policemen also wounded in those attacks on our office. Because I gave the directive straight out, before I went to jail, and after I went to jail in the late part of 1969: "We defend ourselves, because the only thing we are defending is our constitutional, democratic, civil, human right to organize our people, to educate our people, to unite our people, in opposition to the institutionalized racism in America, whether the racist pig power structure, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI don't like it or not. [Expletive] Ôem!" (Laughs) ...

They came down on us because we had a grass-roots, real people's revolution, complete with the programs, complete with the unity, complete with the working coalitions, where we crossed racial lines. That synergetic statement of "All power to all the people," "Down with the racist pig power structure" -- we were not talking about the average white person: we was talking about the corporate money rich and the racist jive politicians and the lackeys, as we used to call them, for the government who perpetuate all this exploitation and racism. That's who [we] were talking about when we said "the corporate pig power structure."

zzzzzzzzzz

http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/cold.war/episodes/13/interviews/seale/

C/S

euthanasia without anaesthesia!

ReplyDeleteFree Palestine! Is real an Palestine should come together in a unified state. Probably not in my lifetime. What is the connection with the Blog Post? Just spamming?!?!

DeleteNigga that's inhumane

ReplyDeleteI am leaving the racist Anonymous Comment up for now. To remind us we will have a lot of sick perverts around. ~Che Peta

ReplyDeletewe're all entitled to an opinion homeslice

Deleteshutup, jew.

ReplyDelete